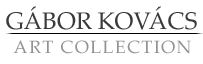

Péter Fertőszögi

Péter Fertőszögi

Introduction To The Collection

Truly significant collections of considerable aesthetic value can only be assembled by people who have a sensitive eye and a cultured, sure sense of judgement, in addition to the desire to acquire and the necessary financial resources. Just as a collector may speak about his treasures, a collection may also reveal a lot about its owner. To posses works of art is basically a question of wealth—to create a real art collection is a far greater and harder task. A conglomerate of works of art heaped together without any concept is merely a variant os financial investment. It only becomes an art collection in the noblest sense of the word when it assumes an individual character, when its items begin to interplay with one another, and when the collection is like a music—a tone can be nice in itself, but no beautiful and elevating music is born unless the composer arrenges the tones in a unity. Thus, a real collector is also a composer.

Gábor Kovács has been buying paintings and sculptures, guided by a longing for beauty and harmony, for some fifteen years in order to create a momentous collection, to compose his own music. His collection spans art from the early 18th century to our day, and consists of over 300 items. So far, he has only collected, but now the moment of systematisation has come involving the decesion about how to continue. In other words, his first collecting period is over.

While painting, in the fever of creation, the painter cannot judge objectively whether what he is doing is good or not. He therefore interrupts the work, puts down the brush and takes a few steps away from the canvas to observe the work. He can see the juxtaposed parts united into a whole and judge the composition more realistically. He can establish what is good and what needs a different approach, then he picks up the brush and continues. An art collector also needs such rests, pauses, to see his collection "from the outside”, to systematize it and decide about the next course to be taken.

This volume presents about one third of Gábor Kovács’s collection, the finest works from the period between 1700 and 1935. Though it does not offer a comprehensive overview of the entire history of painting in those two and a half hundred years or so, it nevertheless has an individual profile and reflects the collector’s personality, tastes and main fields of interest. It is at the same time a tabula rasa. While closing off and synthesizing a collecting period, it stakes out three main courses for the forthcoming years. First, the collection from the 18th century to the Second World War must be complemented. The missing links must be found and other important works purchased to reinforce the weaker points, to create the historical continuity of painting at a high level. Secondly, on this basis a collection of the second half of the 20th century must be built that links the past to the present but also serves as a starting point for the attainment of the third, and most important goal, in support of the efforts of the foundation. This goal is a 21th century Hungarian art collection based on beauty, purity, harmony and mastery.

In his preface, which articulates his ars poetica, Gábor Kovács defines his criteria of selection. All his life has been spent close to nature, he had the opportunity to discover its beauty and potential creativity. Longing for universal values, he is also searching in the surrounding world for the beautiful, the good and the elevating. Hence the main lineament of his collection contains masterful landscapes, with which works on other themes are harmoniously connected.

The range of Hungarian painting from Károly Markó the Elder to the Nagybánya school is represented in the collection almost without fail. In respect of Markó’s works, probably Gábor Kovács’s is the richest private collection. The seventeen paintings not only consitute the most exquisite part of the collection but also give an overall insight into the œuvre. Outstanding among them are the early St. Paul Shipwrecked on the Island of Malta, believed to be lost for many years, Women by the Well, Fisherman, painted during his stay in Pisa, and Inviting of the Followers, which was held in a Spanish private collection for many years and which returned to Hungary only recently.

The extent to which Markó’s sons continued his endeavours is also represented in the collection. The younger Károly Markó’s Waterside Scene or Ferenc Markó’s Before the Storm and Summer display more elements of genre scenes, while andrás Markó’s view of Naples adheres more faithfully to the main characteristics of his father’s style.

The art of the Markó family ties in with developments of Italian landscape painting, while in Hungary in the first half of the 19th century a specifically central European style, Biedermeier, reigned. At home the portrait was the leading type of painting rather than the landscape, as the aristocrats and the rising middle-class personages of the Reform Era wished primarily to have themselves depicted. Masterly representatives of this trend are János Jakab Stunder’s Portrait of Csokonai and János Donát’s Portrait of Dániel Berzsenyi from the early 19th century. Miklós Barabás’s Female Portrait and Mihály Kovács’s Portrait of a Girl display more signs of Biedermeier than Classicism. Even in that half century, however, artists were also inspired to depict more than the facial features and clothing of the models by placing them in a natural setting. The natural background in Donat’s Female Portrait and Sándor Kozina’s painting of the Pejasevics children does not merely indicate the unity of man and nature in an exemplary manner but also illustrated the process in which landscape first came abreast of and then superseded portraits as an independent genre of painting in the second half of the century.

After the failure of the 1848-49 War of Independence, the romantic longing for the past was reinforced. This feeling was expressed in historical themes as well as landscape painting. The outstanding specimens of Hungarian Romantic landscape painting constitute a separate unit within the collection. In addition to Antal Ligeti’s five beautiful canvases abounding in light effects in their depiction of Mediterranean or Hungarian scenery, special mention must be made of József Molnár’s mountain brooks rushing over rocky beds, Gusztáv Keleti’s forest clearing painted down to the minutes details, and Károly Telepy’s three masterpieces. Telepy’s panorama of a sunsoaked Alpine landscape seen through a shady crevice would alone suffice to illustrated the requisites of Romantic landscape art.

Thought Romantic landscape painting ending up in Academism was popular even as late as the turn of the century, several young artists started along new roads. Related to the Barbizon circle, László Paál’s manner of painting forest scenes with their narrow extracts and the treatment of the whole as a large unit define his lifework as the most important chapter of Hungarian Realist landscape painting. Progressing from meticulous detailing towards Naturalism Géza Mészöly became the greatest representative of „paysage intime” in Hungary. Though his soft-spoken pictures of Balaton or Tisza-river settings are related to the Barbizon school, they preserved their Hungarian flavour. Béla Spányi’s and Artúr Tölgyessy’s painting shares features with his art.

László Mednyánszky’s motionless landscapes in the faint glimmer of dawn, his misty, hazy forest interiors and light-cracked mountain peaks turn nature into mystic vision. Starting out from actual natural elements, his blossoming trees and Tátra landscapes convey moods and emotions. His lifework stands alone, without predecessors or successors in Hungarian art history.

The most valuable landscapes at the turn of the century came from the brushes of the Nagybánya artists. It was they who understood Pál Szinyei Merse’s plein air attempts made a quarter of a century earlier and improved upon them to create Hungarian Impressionist landscape painting. Inspired by their approval and affection, Szinyei picked up the brush again to paint a row of sunny landscapes similar to Rivulet Bank.

The Nagybánya segment of the collection needs completing, although it already has several valuable representatives. Outstanding are Károly Ferenczy’s Cross Hill and sunbaked Autumn Hillside, Simon Hollósy’s Landscape around Nagybánya and Rivulet Bank in Spring, János Thorma’s Woman with a Bunch of Violets, Valér Ferenczy’s Grove, András Mikola’s Gallop Course in Nagybánya, Jenő Maticska’s Riverside in Winter and Sándor Ziffer’s three splendid canvases in glowing colours (Nagybánya, Detail of a Park and Garden in Spring).

It is a sign of the diversitiy of painting in the age that in works in Naturalist style one can also discover the influence of Impressionism. Sunny Landscape by Márk Rubovics, Imre Knopp’s Sprong and Gusztáv Mannheimer’s Florence View well exemplify this. Their place in the collection, however, is due to their artistic quality and not to this feature. It is a commonplace that an artist is to be judged by his masterpieces and not by his entire lifework. In addition to the above three works, representatives of the Szolnok school, Sándor Bihari’s Watering the Horses, Izsák Perlmutter’s Street in Laaren and Sándor Nyilassy’s Rowing confirm that artist outside the vanguard of art can also produce high-quality works and they demand their place in collections.

The ramifying tendencies in early 20th century art also had their imprint on Hungarian painting. Artists standing on similar platforms rallied in loose groups only to diverge in quite different directions and accomplish their careers most diversely. István Csók painted his Domestic Agency at a young age, under the influence of French Naturalism, followed by a prolific output of artistic nudes, flower still-lives, impressionistic landscapes and genre scenes, and conversation pieces inspired by the colourful costumes of the Sokac people, all testifying to a virtuosity and rich palette similar to that of Renoir. Csók would repeat a successful composition several times, such as the reclining nude in Studio Corner or the chrysanthemums in folk pottery vases. József Koszta also worked out the same theme in this summary, robust manner, as seen in the collection.

János Vaszary’s lifework, which underwent several changes in style, also started with Naturalism. His three works in the collection aptly exemplify the thematic and stylistic variety of his painting. After a start he shared with Károly Ferenczy, Béla Iványi Grünwald deviated massively from the spirit os Nagybánya towards decorative planarity. His masterfully painted Flower Still-life, created late in his life, is akin to István Csók’s works of the same theme.

As for the Group of Eight, Lajos Tihanyi’s Landscape with a Winding Road attest to the influence of Cézanne. Ödön Márffy’s three works from different periods of his career share the sweeping handling of form, the rendering of the impression of the moment and the rich, light-diluted colour scheme.

The avant-garde trends of the 1910s pointing towards Expressionism are discernible in the pictures of János Mattis-Teutsch. His landscapes built of organic forms but reduced to planes are filled with symbolic meanings. His meandering lines and large, pure colour patches signpost the course towards the ultimate abstraction of landscape elements.

The polar opposite of his art is represented by Gyula Batthyány’s singular, attractive painting. Just like his drawings, his paintings are meticulously elaborated. The startling perspective of his Affluent Neighbourhood and the staggering houses verge ont he caricature, but the rococo charm and ease captivate the eye. His Main Square of Siena is also full of mannerism. He applies the contrast of light and shade to further elongate the oval Gothic square lined with houses in brilliant colours so as to counterpoint more effectively the horizontal axis defining depth at a right angle to the picture plane with the vertical city tower.

Independently of, and partly isolated from developments at home, Béla Kádár’s painting was tied to German Expressionism. In the early Spring Landscape the stems of bare trees and their interwoven branches create rigorous compositional order, the severity of which, however, is alleviated by the soft green hills in the background. His Chamber Music, painted some two decades later, excludes such contrasts. The blurred hazy contours of the figures and the translucent soft colours suggest timeless calm that cannot be upset by the reddish patch of the piano cutting across the picture space diagonally.

The greatest master of Expressionism growing out of the Hungarian soil int he inter-war years was József Egry. His Riverside Landscape, forced between strict outlines, displays the typical features of his early works. In his solitude in Badacsony his new style matured by the 1930s in which colour and form redissolved in all-imbuing light. The pictorial elements became secondary, ready to be disolved in the glowing, vibrating luminosity.

The spirit of Nagybánya lived on in the work of István Szőnyi. He collected the motifs for his pictures in the small Danube-side village of Zebegény—from the picturesque scenery and the everyday life of the people living there. Without meticulous details, he created his large compact forms from loose patches permeated by the tranquillity of peace and silence. The main lineament of his painting is taciturn simplicity—he could say much with few words. The reserved colours of his pictures based on the tempera technnique further enhance the monumental effect.

Similarly to Szőnyi, Károly Patkó and Vilmos Aba-Novák also started in Nagybánya. Patkó’s emphasis on the plasticity of form is coupled with more powerful colouring. The colourful houses peeping through the stems of trees int he foreground in his View of Nagybánya and the threatening large dark block of the mountain behind them are elements of masterful spatial composition. His light-soaked powerful colours with bluish-purple shadows further enhance the dramatic effect. Aba-Novák trod along the same course until he went to Rome on a scholarship in 1928. He was captivated by the teeming life of small medieval towns creeping up the hills and merry turmoil of Mediterranean life. The houses of his Italian Townscape like buildings blocks and the widely gesturing figures mark a new period in his art. This painting is an important item not only in the collection but also in Aba-Novak’s entire œuvre as it is a precedent for his Promenade Concerto f 1929.

The selection ends with an early masterpiece by István Boldizsár and one by Frigyes Frank. This is not accidental, as their efforts point beyond the 1930s and at the same time constitute the foundations of a collection representing the next decades of the 20th century.

Every serious art collection has key works, major works of art and complementary items, but rare treasures are found only in the truly significant ones. Ádám Mányoki’s portrait of the wife of Ferenc Rákóczi II and János Kupeczky’s Man with a Lute are notable pieces of Hungarian Baroque painting from the first decades of the 18th century. Mihály Munkácsy’s decorative Flower Still-life and Lajos Gulácsy’s Female Portrait of a Secessionist atmosphere painted in Florence are precious pieces. József Rippl-Rónai’s Fisherman’s Cottages is one of the sixty pictures or so painted about the life of a small fishing village during an excursion to Banyuls. Undoubtedly one of the most precious treasures of the collection is Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka’s Mysterious Island. The elementary force that emanated from Csontváry’s whole being and from each of his creations radiates with a sweeping effect from this small-sized painting.

In recent years more and more works in private collections are introduced through representative albums and exhibitions. The public can have a glimpse of valuable works that were previously hidden. The aim of this book is also to make it possible for all those who love fine pictures, not only for their owner, to take delight in the works of art of a significant private collection.

(Source: A Kovács Gábor-gyűjtemény / The Gábor Kovács Collection. Ed.: Fertőszögi, Péter – Kratochwill, MImi. Vince Kiadó, Budapest, 2004. pp. 37-41.)

László Tolcsvay

Collection What do you collect? Why do you collect?

What do you collect? Why do you collect?

You collect experiences, feelings, knowledge, friends, possessions—innumerable tangible things and ones that only the spirit can sense. This collection is what constitutes your life. This is what you try to arrange, line up, classify, and transform in your soul, so that you can build your own individual existence, the reason for this time on Earth. If this is how you look at human life, then everyone is in truth a collector. We collect spiritual and material supplies.

It does matter which shelf of your soul you use to store your collection. It does matter which experience, mosaic of knowledge or feeling—which gem of your spiritual treasures—you have at hand to answer a question life poses. And at the end of the journey, the true value of your entire collection will be revealed to you.

A unique case of collection is when the joy of discovery, the thrill of looking for rarities, the ecstasy of the find, become a passion. Its motive force relies on a balance of instincts, talent, knowledge, education, playfulness, luck, perseverance and patience. This is what makes the collection personal and individual. This is what makes it enduring.

Accessing such a collection, whether at an exhibition or in virtual reality, gives rise to the hope of getting to know the collector. Because this selection is informed by the personality. We can wonder at his intentions, intuit his thoughts and feelings. We can get closer to his soul. A great opportunity.

Those who have visited Gábor Kovács in his home or at the Bank Centre know that before discussing the matter at hand, he will show his latest treasures. Not only because he is proud of them, but also because he is ready to open up. They are his calling card. He might as well say: “Look, there I sit at that table, in that company; there I stand on that summit, listening to the rustle of leaves; there I am in the blossoming spring; there I fly with that angel.” This is the most important. Because he does not merely see the aesthetic in the works of art, but he responds with his soul, looking for a lead through which he can enter into an alliance with the spirit of the artist. This is why we can claim his collection is more than a mere pastime. In addition to the original affinity, he has been building a very conscious collection, for a long time. He does so while not giving up on the joy of the free spirit, the committed respect for beauty. Among other things, it is the fruit of his passion that several of the works by Hungarian artists which are now his prized gems were previously latent in foreign collections.

This collection allows us to get close to the soul of the collector. The paintings, sculptures, tapestries and graphic works are now the messengers of Gábor Kovács, which allow him to show us his feelings, experiences, knowledge and thoughts. And if you listen carefully, you may find that through these works of art he will answer questions he would not answer in an everyday conversation.

So we should not only look at these masterworks with attention, an open soul and sensitivity, and delight in the greatness of their creators, but we should also accept them as something that allows us to understand the original vector of the collector’s passion. With an open heart, we may sense the mystical power that attracted him to these works of art, that makes him want to live with them. Let us gather the wonder that radiates from these pictures and reaches us. Let us sense the spiritual field that had such an effect on their owner. And then we can realize Gábor Kovács collects not only for himself. Should this not be the case, he would keep his pictures in a safe, and would look at them on his own, with some great wine reserved for the purpose.

Luckily, this is not how things stand. He is passionate about showing us his treasures. With the honesty of a child, he delights in, and dreams about, the prized pieces of the collection, again and again, every time he shows them to the initiated viewer. With invisible spiritual fluids, he spins the filaments that attach his soul to a work of art. On such occasions, he is dreaming awake.

One of the most attractive manifestations of his dreams come to life is KOGART. Gábor Kovács founded this establishment to provide a worthy scene for the enjoyment of art. The power and faith that created this citadel of art on Andrássy Avenue, in Budapest, Hungary, Europe—he fostered these in his soul with the uplifting, thought-provoking, delightful radiation of the works of art.

A brilliant achievement.

Let us express our gratitude!

I am certain that his affection for the visual arts owes much to those profound childhood experiences of the Great Plains. I know because I heard him talk with affection about his birthplace, Kakasszék.

Interestingly, and not incidentally, I was in Florence when Gábor first asked me to open a comprehensive exhibition for which he himself selected the works from the collection. Florence, the city of Cosimo and Lorenzo Medici. The city that is almost exclusively about art. The capitol of Tuscany is in effect a vast collection—of talent, humanity, beauty and the creativity of humankind. A visit there is an uplifting experience because the soul and spirituality of the creators have remained – carved in stone, painted on the wall, towering as a campanile. This city is the absolute testament to how only art can survive the inevitable passage of historical epochs.

This is why it is a sign of wisdom to use art and culture as a means to open one’s will, talent and wealth towards universality: it is a way of building, creating, delighting and bringing succour to the soul—and hence a way of creating real wealth. For all of us. Whether in Florence, Budapest or Kakasszék.

Such a real collector will know and profess that art is eternal.