László Tolcsvay, composer

László Tolcsvay, composer

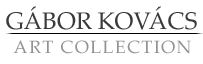

Mysterious Island

(On Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka's Mysterious Island)

Being a musician, I’ll forbear dabbling in art criticism and want to relate only the excitement and calm that filled my heart when I saw the picture.

You cannot tell whether the storm that batters the island on the canvas is coming or going. My impression is that it has just arrived, but the sun is already shining behind the clouds. Otherwise the small sailboat, full of hope, would hardly have ventured out to a sea whose surface is still unruffled. The merry-go-round of the riders on the wall is already bathed in light.

Nor are the mysterious creatures of the island troubled by the tempest. They are dancing, knowing there is no danger because sunlight glows in all of Csontváry’s pictures, and it will always give warmth to the small realm behind the walls.

What else could encourage the angel-anointed Hungarian genius of the “way of the sun” for creative work?

A monastery is also a mysterious island, as isolated as Csontváry’s dream surrounded by the sea. If the world outside is now tempestuous, now peaceful, ceaseless prayer within guards the truth.

I had seen the monastery in Bánfalva before the reconstruction, ruined, looted, disgraced, abandoned. I am always saddened when the faithless destroy something, acting on barbaric impulses, creating an inarticulate frenzy around themselves. They do so because, hiding in the tempestuous darkness of their souls, they think they are invisible.

There is, however, one thing they forget. There will always be someone who is watchful, in whose heart trust and hope, the “way of the sun,” feed an undying fire. When the opportunity arises, he will collect his allies and march his perfervid knights to serve salvation and talent. He will build, reform, create. To the glory of God.

Here I stand, with a rapturous heart, under the beams of the Novitiate Hall, which are decorated with ancient motifs, and I feel that from now on the same sun will shine on us again that shone on the Paulists.

Fiery and bright, as if the storm had left the island on Csontváry’s painting for good.

Grace shines in the hearts when someone creates with an elevated soul, full of virtue and faith.

Zoltán Cser, Buddhist teacher

Zoltán Cser, Buddhist teacher

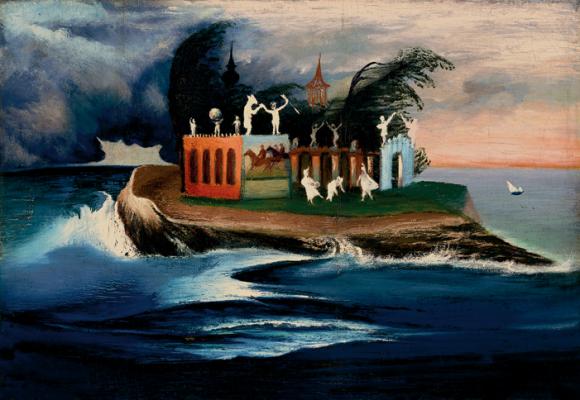

Crimson and Emerald

(On Lajos Gulácsy's Crimson and Emerald)

Looking at man, we can observe two types of action. First, we have hands and feet, so we can manipulate and walk, just as we have organs that enable us to talk or song. Sensation is the other type of action, most of the organs of which are situated on our heads, arranged vertically in a particular order, with the eyes on top, etc. As the eyes can see, so the soul has a way of looking at things. What I mean is that our selves exist in mostly in images, our nature is defined by visions, memories, worldviews and outlooks. There are, in other words, many types of images, some of which can be found in the deepest recesses of the soul, which we can call symbols or archetypes. Archetypes are very important at times when humanity forgets about fundamental ethical values, has no respect for other humans, for nature, creation and beauty, engaged in an endless rush that only destroys man and his environment, whilst becoming more and more superficial spiritually. Archetypes are there to warn us that man is but a minute part of nature; it is possible to live in harmony with it, and it offers its wonders for contemplation as a young girl contemplates the archetypal images of the sunset or the sunrise on a windswept beach. Whether it is a sunset or the sunrise, it is impossible to tell, the colours whisper, sky, sea, land, they have another miracle as a part, man, we only need to learn to stop. Crimson and emerald, crimson and emerald. We need to learn to stop.

László Hollós, Buddhist teacher

László Hollós, Buddhist teacher

Diptych

(On Béla Kondor's The Prophet)

I know they are not one.

They are not even contemporaneous. Merely brought

together by chance.

They are nonetheless like one, belong together

in my eyes like the two pictures of a diptych.

Departure and arrival.

The red and gold lights of dawn, the ecstasy of hearing the word uttered,

the sunlight halo radiating from the fingers of the raised hand.

The state of creation.

Power, will, confrontation, action. As if he grabbed the axis

around which the world turns.

The cool blue of sunset.

The motionless calm of arrival.

The wings are not opened for soaring, they no longer serve

leaving the earth behind.

They mark the direction: the way is upwards.

On the figure of the prophet, the pattern of the skeleton of the mortal body.

On the body of the angel, the force lines of a crystal structure

invisible to the eye.

Calm, understanding, brightness, balance.

He no longer wants to change the world: it is he who has changed.

He has found his place.

He is the axis around which the world turns.

The one who will move on is the one he still holds in his arms.

He will set out to travel the new cycle.

He will be the new Prophet, and he may become the new Angel.

Csaba Asztalos, M. D.

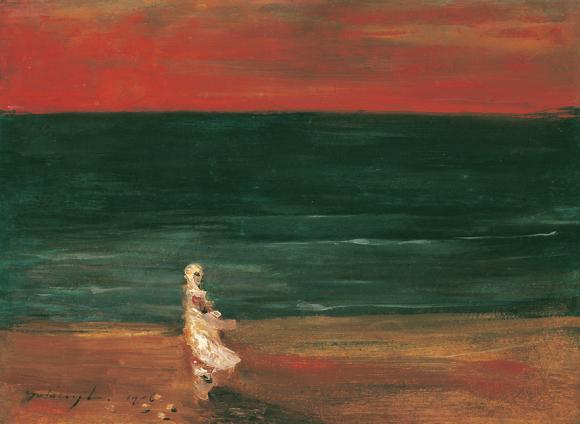

Icarus Tree

(On Menyhért Tóth's Icarus Tree)

I was a bit anxious when I arrived at the monastery, having presumptions of a great experience at the exhibition. While I reach the Novitiate Hall among the ancient walls, passing the yard, the fountain, the cloister, I am overwhelmed by the past, the spirit of history. Bygone times whisper from every nook, and I feel as if the hermit monks had made this a condition to have the experience: I must leave the outside world, earthly being, behind.

I enter the Novitiate Hall (for me, it is not an exhibition hall – it would be unworthy of the place to call it so) as a foreign onlooker, but upon seeing the beams, the carved ornaments and symbols, the pictures on the walls, it all looks familiar!

I get under its influence, I am under its influence!

I stand before Menyhért Tóth’s pictures, musing, unaware of the passing moments... I should remember my life, I do not need to accept this, but here even the insensitive starts feeling, the faithless suddenly starts believing. I begin to envy the monks who once lived here: theirs was a life permeated with intellect, the profundity of ideas, as are these works of art. Looking at them, I see into the world and lives of the “invisible travellers.” In the Novitiate Hall, before the works, I am ready to believe that art is divine creation, the reflection of human and divine ideas and messages, the way to sense depthless being, help to experience the ways of “dimensions.” Nothing is spelled out, this art only presents and invites us to confront, yet anxiousness and order rule the pictures, reinterpreting the sense of mortality. It intensifies my desire for peace and harmony, because we live buried in the world we create. With He who walks on water, I could sense the radiation of that higher world, spirituality, which defines our lives and fates.

For a work of art to be able to represent the experiences and emotions of the human spirit, it does not need to comply with any written or unwritten rules. Whether their tools were simple, even naive, or pointed towards abstraction, the two works led me to the spiritual, magical ideas of being.

Péter Müller, author

Péter Müller, author

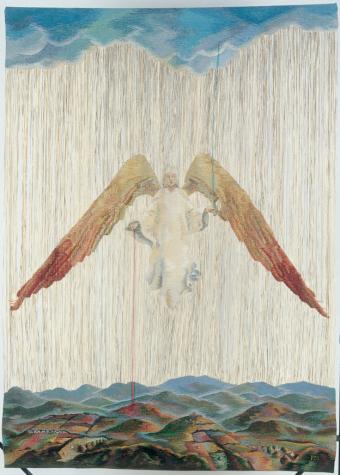

Aequilibrium

(On Zsuzsa Péreli's Aequilibrium)

You cannot, you must not, talk about a picture.

I have always considered it a vain and foolish attempt to exchange

the message of an Image for the small coins of words.

It spoils the work.

An image conveys more than ideas and emotions:

an image conveys an Image.

*

Stop before Zsuzsa Péreli’s gobelin, Aequilibirum.

And look.

Forget where you are. Forget the other pictures, drawings, paintings,

the people around you – and look.

And see!

Do not think of anything, do not feel anything, and above all,

do not try to convert in yourself your experiences into words,

because you will immediately kill the magic of the work.

After a while – if you look and see correctly –, the distance between you

and the work will disappear.

You enter the image.

You become the Angel.

Earth and Sky will also be a part of you.

Your two hands will become the hands of the Angel.

One is the Earth-hand, the other the Sky-hand.

You can feel the mystery of the thread on your fingertips.

You hold the Universe together.

You do not need much.

Two thin threads will suffice.

An Earth-thread and a Sky-thread.

And you?

You, the Angel?

You float.

To hold the Universe together – it is easy.

A trifle.

And as you lead what it above into what is below, and what is below

into what is above, you have a very rare experience.

You find calm.

A calm you have never had.

This is not human calm.

Or angelic calm.

This is Divine calm.

Now you can take your eyes off the work.

You can even forget about it, if you like.

You have become the Angel.

*

Masterworks redeem the soul.

Tibor Almási, art historian

Tibor Almási, art historian

Aequilibrium

(On Zsuzsa Péreli's Aequilibrium)

Commonly called the “grand dame” of modern Hungarian textile art, Zsuzsa Péreli has earned the epithet with an oeuvre which over the decades revitalized this means of self-expression, a form that boasts a venerable tradition in her country’s art. The development of Péreli’s inimitable, unmistakable art has been continuous, its trajectory unbroken. Since as early as the beginning of the 1980s, her original vision and her pioneering work, which sought to reform, as well as to find recognition for, the genre, have been repeatedly acknowledged with professional honours and awards. In 1980 she won the main prize of the Wall and Space Textile Biennial, and its special prize in 1990; in 1981 she was awarded the Munkácsy Prize, and in 1998 the For Hungarian Art Prize; in 2008 she received the Artist of Merit of the Republic of Hungary Award; and in 1994 she was elected a member of the Széchenyi Academy of Literature and Arts.

Zsuzsa Péreli’s early work seeks to evoke the mood of an early-20th century milieu by transposing yellowed, tattered photographs into an artistic medium. She went on to apply objects to the tapestries, which were somehow typical of their age and contributed essentially to the meaning of the works, while also functioning as atmospheric elements. These works opened new directions for the genre, investing the tapestry with the standing of an art object. As in the case of many more artists, the political transition brought a fundamental turn in Péreli’s work. The elements and experiences of physical reality gave way to a different creative intention, one that sought to reflect a different world view. An essential aspect of the latter is a departure from the everyday towards the sublime, towards sentiments that can be experienced in the spiritual sphere. The works of this period translate these feelings into the formal idiom of textile, and are dominated by icon-inspired representations of the Madonna, and other emotionally charged pieces of a more solemn mood, with more abstract subjects and messages. Aequilibrium, a large (220x160 cm) tapestry made in 2000–2001 is one of the fist, and still one of the most beautiful, pieces in this series, a compelling demonstration of the artist’s unique sense of calling. The very arrangement of the composition answers to the appeal of the titular equilibrium, with a formal harmony of vertical and horizontal structures. The very definite horizontality of the dynamic blue sky, which directs the gaze, and of the hilly land that occupies the lower section of the work, is balanced by the perpendicular, brownish woollen threads that suggest a region between the heavens and the earth. It is in this carefully considered and visually harmonic frame of a landscape that the vehicle of the work’s intellectual content appears: an angel with vast wings who hovers between heaven and earth, linking the material world with the transcendental, the physical with the spiritual. In addition to its central position, the angel’s role of establishing a connection is further emphasized by a straight blue and red ray or line that connects its hands with the sky and the earth, respectively. According to the symbolism of colours, blue represents the intellect, a spiritual, superhuman, heavenly force, while red signifies life and mortality, worldly existence. From this perspective, Aequilibrium has multiple layers, admits different approaches and interpretations. It is probably fair to assume that Péreli intended this impressive and spectacular composition to be a reminder in this overly material-minded world that more is necessary for a complete life and the much-treasured self-realization than earthly goods and pleasures: while maintaining moderation and a balance, we must fully embrace the possibilities that a spiritual life offers.

(Published: Almási, Tibor: "Péreli Zsuzsa: Aequilibrium". In: Jog, állam, politika, year IV, 1/2012. pp. 163-164.)

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Ino and Melicertes

(On Markó, Károly the Elder's Ino and Melicertes Tumbling into the Sea)

Greek mythology was one of the Hungarian Romantic Markó's central subjects. In the myth Melicertes dies, when in a frenzy his mother Ino throws him into a basin with boiling water. Having composed herself again, Ino recognises her deed and together with her beloved child's body she throws herself of a cliff into the sea. Mother and son then become the sea gody Leucothea and Palaemon.

János Jerneyei Kiss, art historian

János Jerneyei Kiss, art historian

Charlotte Amalie

(On Mányoki, Ádám's Portrait of the Wife of Ferenc Rákóczi II, Charlotte Amalie, Princess of Hessen-Rheinfels)

— Translation coming soon.

(Published: Vonzások és változások / Affinities and Transformations. Exhibition catalogue. Ed.: Fertőszögi, Péter–Szinyei Merse, Anna. Budapest, Kovács Gábor Art Foundation–Hungarian National Museum, 2013. pp. 5-6)

János Jerneyei Kiss, art historian

János Jerneyei Kiss, art historian

Fruits, birds

(On Jacob Bogdany's still lives)

— Translation coming soon.

(Published: Vonzások és változások / Affinities and Transformations. Exhibition catalogue. Ed.: Fertőszögi, Péter–Szinyei Merse, Anna. Budapest, Kovács Gábor Art Foundation–Hungarian National Museum, 2013. p. 6)

Gabriella Szvoboda Dománszky, art historian

Gabriella Szvoboda Dománszky, art historian

Csokonai

(On Stunder, János Jakab's Portrait of Mihály Csokonai Vitéz)

— Translation coming soon.

(Published: Vonzások és változások / Affinities and Transformations. Exhibition catalogue. Ed.: Fertőszögi, Péter–Szinyei Merse, Anna. Budapest, Kovács Gábor Art Foundation–Hungarian National Museum, 2013. p. 32)